Hello, and thanks for subscribing to, or stumbling upon, this semi-regular newsletter written by me, Ashley Clark, about whatever happens to be loitering in my head at any given moment (usually art/film/music/literature/football.)

As per usual, a quick recommendation to kick off: the short yet sharp and informative book A Brief History of Black British Art by the critic, curator and researcher Rianna Jade Parker. This recently released volume comprises an illuminating overview essay to begin, followed by brief biographies of—and a reprint of one signature work by—63 artists and/or collectives, including John Akomfrah and Black Audio Film Collective, who I’ve featured previously in this newsletter. The cover image is 1972 oil painting “The Lesson” by Jamaican-born, London-based artist Errol Lloyd.

One of the ways I’ve used this space so far is as a home for work that has either never been published online, has vanished from the internet, or exists in a less than optimal form*. I wrote the following feature back in September 2014, two months after I moved from London to New Jersey, for the publication The L Magazine, a New York-centric bi-weekly arts and culture freesheet which sadly closed its doors in July 2015. The piece, commissioned by Mark Asch, and entitled ““Retro Metro” and the Golden Age of Graffiti”, was inspired by—and a partial preview of—the excellent repertory film series Retro Metro that took place at Brooklyn’s BAMcinématek from September 26—October 5, 2014. For the purposes of this newsletter, I’ve made a few minor edits, added some new links and images, and removed some references to the film series, which is now no longer to be anticipated, but a thing of the past. I enjoyed researching and writing this piece at the time, and I hope you get something out of reading it today.

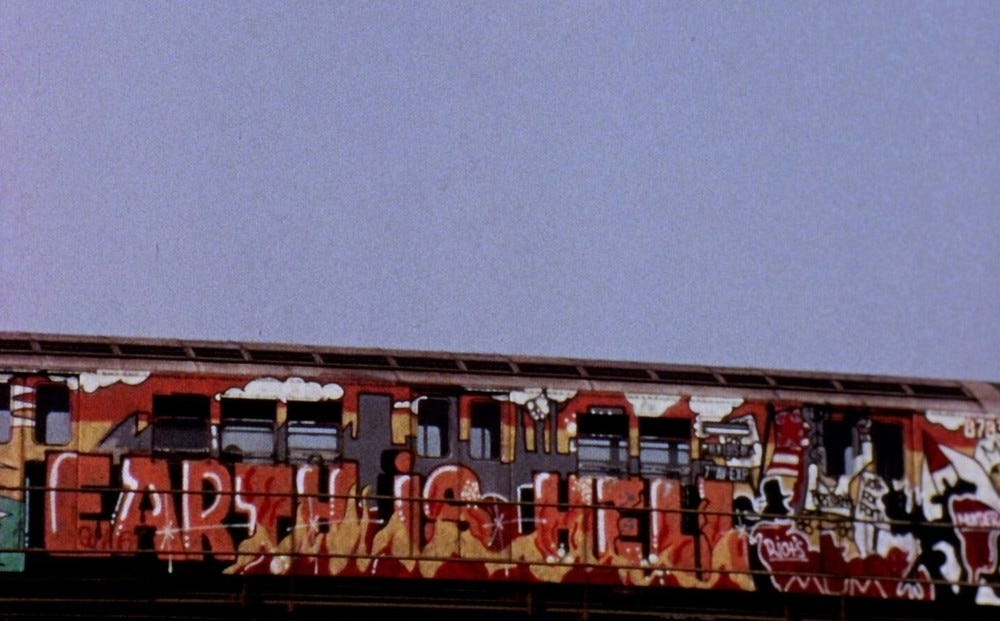

Though New York City’s subway has a long, proud, and occasionally smelly history, it’s the golden age of graffiti art that constitutes its most iconic era in terms of cinematic representation. Subway graffiti was ubiquitous from the early 1970s to the late ‘80s, and showcased a variety of tags and designs from local, mostly Black and Latino youngsters with tags like TAKI 183, Tracy 168, DONDI, and Lady Pink. Broadly speaking, these artists were either lauded in hipper circles for their artistry (see Norman Mailer’s floridly pro-graffiti 1974 book The Faith Of Graffiti), or vilified by the establishment as vandals.

The explosion of subway graffiti in NYC began in the early 1970s, and quickly became a political issue: by 1971, the city was spending $300k per year to erase it. Mayor John Lindsay saw graffiti as a pathological problem—the New York Times reported his belief that “graffiti writing is related to mental health problems”, and his description of the writers as “insecure cowards” seeking recognition. By 1973, a new anti-graffiti task force had been installed, and spending rose dramatically. In spite of Lindsay’s fulminations, and the rise in popularity of the art form, subway graffiti had yet to fully impose itself on cinematic representations of the city. The carriage interiors in Michael Winner’s dubious Death Wish (1974), for example, are conspicuously spotless: it’s the glowering human scum, to be vanquished by Charles Bronson’s vigilante Paul Kersey, that are dirtying up the trains.

The use of subway graffiti as a visual place-marker in cinema rose under the consecutive tenures of firstly Mayor Abe Beame—who was forced to slash the struggling city’s budget in a bid to stave off bankruptcy—then Mayor Ed Koch, who was sworn in in 1978. Yet some filmmakers transcended the use of subway graffiti as simply local coloring. In John Badham’s Saturday Night Fever (1977), graffiti is used as a poetic backdrop for its characters’ psychological states. Consider the scene in which white-suited jiver Tony Manero (John Travolta), in a maudlin mood, languishes in a carriage. A huge splurge of claret paint suggestively haloes his head. In another shot, the scrawled black tags hover over his bouffant like jagged thought bubbles. In compositions such as these, we see manifest the description of graffiti offered by hip-hop scholar Fab 5 Freddy in his foreword for Bruce Davidson’s classic Subway photography series: “a tornado of multicolored, mural-like extravaganzas on the outsides, while interior signatures became an abstract of Jackson Pollock-like drippy calligraphic madness.”

There’s a similar moment in Walter Hill’s The Warriors (1979)—perhaps the ultimate NYC-subway-as-narrative-function movie—when a group of peppy prom kids hop on the train, and sit opposite our dirtied, exhausted lower-class antiheroes. In the absence of dialogue, all we have to go on are charged glances and the hieroglyphics on the wall, which speak to characters’ difference in class and status. The scene echoes Fab 5 Freddy’s observation that “the graffiti on the trains began to decode itself when people sat in front of it, like Medusa coming to life.”

In the Beame and early Koch eras, there had been little press coverage of graffiti in the media, which reflected the city government’s reluctance to publicize its continued failure to exert control over the phenomenon. Yet this blackout ended in 1980, when the Times Magazine published a feature on three writers: NE, T-Kid and SEEN. SEEN is a key figure in Tony Silver and Henry Chalfant’s Style Wars, a thrilling documentary which premiered on PBS in 1983, but was filmed in 1980 and 1981. Ostensibly a study of the three pillars of hip-hop culture (graffiti, breaking, and hip-hop/DJ’ing), Style Wars zeroes in on the “taggers” and “bombers”. Its title is a model of punchy multivalency, referring simultaneously to battles between youth and establishment (Mayor Koch, who dubs graffiti a “quality of life offense”, and ramps up anti-graffiti spending, is the film’s arch-villain); between parents and children; and various intra-subcultural rivalries.

In a similar vein to Jennie Livingston’s drag ball scene study Paris Is Burning (1990), Style Wars is a rare example of a formally interesting documentary which attempts to capture the texture and entire arc of a subculture. One thrilling sequence sets a rapid montage of SEEN’s vibrant, large-scale train art to the rollicking swagger of Dion’s 1961 rock n’ roll hit “The Wanderer,” effectively melding an aural signifier of one generation’s subculture with the visual signifier of the next.

Style Wars shows how graffiti writing was fetishized by the artists, who were attracted by the elements of danger. One artist almost licks his lips when speaking of “live rails, crazy cops, the smell of trains”. The film also broaches the charged racial dynamics of the scene: consider the telling moment when a dweeby white tagger in a Van Halen shirt admits to a love for robbing paint, but perspicaciously confirms that it’s much harder for Black and Puerto Rican kids to get away with it.

Notable, too, is the inclusion of footage from cringeworthy, ingratiating anti-graffiti PSAs starring boxers Hector Camacho and Alex Ramos (“Take it from champs, graffiti is for chumps!”), and Fame stars Irene Cara and Gene Anthony Ray (“Use your head, or your voice, but don’t waste your time making a mess!”) The co-option of mainstream cultural stars to criticize a subculture is frequently a sign of its impending doom.

Style Wars ends on a double note of ruefulness. Firstly, it spotlights the early days of the commodification of street art, with graffiti easing from the subways into Manhattan’s art galleries. Then there’s Mayor Koch’s announcement of a $1.5m program to provide barbed-wire fences and German shepherd watchdogs for the Corona rail yards. (Months later, Koch announced that the city would increase the city’s contribution to the MTA by $22.4m in order to fund the installation of similar fences at 18 other yards.) Yet Style Wars’ spiritual denouement is a stunning, uninterrupted left-to-right pan of an entire subway train daubed in colorful murals, tags, anti-war slogans, and personal pleas. If people wanted to know what the youth responsible were thinking, it was all there, on the trains, plain as day.

This heart-on-sleeve-on-trains earnestness is apparent in films like Charlie Ahearn's Wild Style (1983), with its much-sampled “Subway Theme”, and Stan Lathan’s urban melodrama Beat Street (1984), which was released in the same year that two key things happened: the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) began a five-year, “die hard” program to eradicate graffiti; and Bernhard Goetz, a decade on from Death Wish, became a vigilante-style “folk hero” in certain quarters for shooting four unarmed Black kids on a subway.

With its story of two friends eking out a living on the hardscrabble South Bronx streets, Beat Street is a feature-length testament to the fiscal, social and corporeal difficulties of pursuing subway graffiti writing with any sort of vigor. The quietly driven Kenny (Guy Davis) is a budding musician, while his Puerto Rican pal Ramon (Jon Chardiet), much to the chagrin of his desolate father, is dedicated to decorating trains. “My tags are running in Brooklyn, The Bronx, Queens, right now, in every borough, on every line,” he opines, “It’s eight feet high and it’s beautiful!” Ramon is finally tempted by a virginal white train—modeled on Koch’s short-lived “Great White Fleet”—and sets about leaving his mark, only for his nemesis, overwriter Spit (based on Style Wars’ villainous destroyer Cap), to immediately deface it. After an ensuing chase and struggle, poor Ramon is terminally frazzled by a live third rail, in effect dying for his art.

Beat Street is a generally solid and enjoyable film, but there is one sliver of genuine visual poetry: when Ramon’s casket is driven away, the camera tilts up and pans right, simultaneously matching the hearse’s exit from the lower portion of the frame with a graffiti-strewn subway train barreling across an overhead bridge. Where is his spirit, this composition seems to ask: in the hearse, or splayed across the side of the train? Presciently, the film treats Kenny’s musical dreams as infinitely worthier of time and investment than Ramon’s spray-can endeavors. Indeed, it was hip-hop, rather than graffiti, which went gone on to become the multi-million dollar empire.

If Beat Street missed the boat on graffiti’s salad days, then 1985’s Turk 182!—its name a risible riff on Taki 183—sputtered out on the way to the pier. Timothy Hutton stars as the eponymous tagger, a spunky 20-year-old who mounts a graffiti campaign in an effort to redeem the reputation of his brother, a heroic fireman dismissed from his job by an unfeeling city bureaucracy. His limp reign includes leaving his mark on a supposedly graffiti-proof subway car to be used by the fictional Mayor Tyler in an anti-vandalism campaign. The film—which critic Dave Kehr described as “deliberately designed to drive you screaming from the theater”—serves as a living reminder of the horrors of mainstream appropriation of a subculture.

Under the auspices of President of the New York City Transit Authority David Gunn, who launched the “Clean Trains” initiative, the MTA systemically, train line by train line, took the subways off the map for graffiti writers. If graffiti artists “bombed” a train car, the MTA would yank it from the system, even during rush hour. On May 12, 1989, the last graffiti-daubed train car was pulled from service: this was declared the official day of the city’s victory over train graffiti. By the time of Leslie Harris’ sparkling indie comedy Just Another Girl on the IRT (1992), the subway cars traveled on by our heroine, independent 17-year-old Brooklynite Chantel (Ariyan Johnson), are pristine.

Of course, there is still subway graffiti today—it just never leaves the train yards. Artists paint subway cars knowing that they’ll be cleaned before they’re ever seen by the public. The live third rail, too, continues to claim lives. In December 2013, graffiti legend Jason Wulf—who tagged as DG—was electrocuted at 25th Street Station in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. Just as artistry and tragedy endures, so does a fascination for the era. Manfred Kirchheimer’s extraordinary, recently restored 1981 documentary Stations of the Elevated takes a reverent, classical approach to subway art, with shimmering 16mm images set against a soundtrack interweaving ambient city squalls with the roiling jazz of Charles Mingus. Unseen for decades, Stations is a fitting testament to an art form—and an era—which remains internationally iconic.

*Full disclosure: when I had the idea to revisit this piece, I thought it had disappeared from the internet—it certainly had disappeared once, when I looked for it a couple years back. As of now, it’s archived, but is awkwardly broken up over two web pages, only has one image, and features a couple of horrible typos and overcooked turns of phrase—my fault!

Thank you for reading. Please consider subscribing to this newsletter if you’ve yet to do so, or, if you have, spreading the word. I appreciate it!