Hello! Thank you for signing up to, or stumbling on, this no-news-newsletter written by me, Ashley Clark. If you do choose to subscribe—and it’s free—you’ll receive bulletins about whatever’s on my mind: usually some combination of art/film/music/literature/football. If that sounds good, hit the button!

In last week’s letter, I said I was taking a short break, and that there wouldn’t be another edition until the new year… but I lied. Why? Because Pelé died. I knew he wasn’t well for a while, but I still got a shock on reading the news of his passing. Put simply, Pelé was one of those people who I just assumed would be around forever, like Bruce Forsyth.

Anyhow, a few years back, during my time as a freelance journalist, I wrote an article for the Guardian about the half-decent Pelé biopic Pelé: Birth of a Legend (2016), and, more interestingly, his surprisingly robust track record as a film actor. I’ll leave the real tributes to the experts—this is a terrific piece by Jonathan Wilson, for example—but hopefully some of you might find the following of interest. I’ve given it a very light edit, added some new links and images, and repurposed below.

Originally scheduled to appear in time for the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, the long-delayed Pelé: Birth of a Legend—the first ever biopic of the football icon—is finally being released. Co-directed by American brothers Jeff and Michael Zimbalist, and executive produced by Pelé himself, the film unfolds like a superhero origin story crossed with a sporty riff on Slumdog Millionaire.

Its first half charts 10-year-old Pelé’s hardscrabble existence alongside friends and family in the slums of São Paulo state; its second focuses on his rapid rise to prominence with the Brazil soccer squad, culminating in his team’s victory at the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, when Pelé was just 17. (Pelé scored twice in a 5-2 win over the Swedes, here clumsily portrayed as a swaggering battalion of Aryan Terminators.)

Curiously, despite the film’s Brazilian setting, all its characters are fluent in English. This is presumably a ploy to enable the film to reach the widest possible audience, but it never stops being jarring. The weirdness factor only intensifies when Vincent D’Onofrio, the burly American star of Netflix’s Daredevil, pops up to portray Brazil’s under-pressure coach Vicente Feola. The actor’s Brazilian accent frequently strays, volubly and hilariously, into Al Pacino-in-Scarface territory.

Though the film is overly simplistic and often hackneyed (one could easily lose count of the number of sun-kissed training montages set to twinkly music), it’s rarely dull, and there are some interesting revelations. We discover, for example, that Pelé (born Edison Arantes do Nascimento), received his indelible nickname from a rival child footballer and initially loathed it. The filmmakers also deserve credit for addressing racism and classism in Brazilian society, and how these issues manifested in heated debates over the efficacy of Brazil’s joyful, “primitive” style of soccer.

Proceedings are further elevated by charismatic performances from the two young actors playing Pelé (first Leonardo Lima Carvalho, then Kevin de Paula), and the stirring presence of Brazilian superstar Seu Jorge (City of God) as Pelé’s taciturn yet warm father.

Near the end, Pelé himself contributes a brief, amusing cameo. Perhaps the film might’ve been improved by a more substantial appearance from Brazil’s record goalscorer. After all, as the following examples show, Pelé has a surprisingly prolific record in front of the cameras.

While still playing professionally for his club side Santos in Brazil, Pelé racked up an impressive list of acting credits. In 1969, he played an alien named Plínio Pompeu in The Strangers, a sci-fi TV show designed to drum up national interest in the Apollo moon landings. Two years later, he appeared briefly in the ribald, Benny Hill-esque sex comedy O Barão Otelo no Barato dos Bilhões, projecting stately authority as a suave doctor who comes to the financial aid of the film’s main character, a diminutive would-be playboy.

Pelé’s most interesting early role, however, came in Osvaldo Sampaio’s period drama A Marcha (1970), which was set in the final years of Brazilian slavery. Pelé played an abolitionist named Chico Bondade, a Scarlet Pimpernel-type freedman who infiltrated plantations to free slaves in the 1880s.

After his retirement from football in 1977, Pelé redoubled his commitment to national, political cinema by appearing in Anselmo Duarte’s action-packed, Blaxploitation-influenced drama Os Trombadinhas (1979). In his 1998 autobiography, Pelé wrote: “I especially liked [this film], and collaborated on the story for it. It was about the problem of abandoned children; a subject I cannot repeat often enough is close to my heart. I hoped the film would help get them off the streets, make something useful of them, for them and for society.” (Pelé also found time to contribute vocals to a couple songs on the soundtrack: he’s no Gilberto Gil, but his vocal stylings boast a certain calming trill.)

In 1981, Pelé gave his highest-profile film performance as Corporal Luis Fernandez in John Huston’s POW adventure Escape to Victory. Pelé’s involvement arose as a spin-off from his contract with Warner Communications, who owned the Warner Bros film studio. Of working on the film, Pelé’ wrote: “I’d come onto the pitch with the same passion that I had brought to real games… Huston used to shout, ‘Pelé, relax! It’s a film, it has to be contained within the scene, the emotion has to be controlled…’ He was a cinematic genius.” He also threw some shade on co-star Sylvester Stallone: “I learned too that the ‘stars’ don’t always work democratically. Stallone, for example, wouldn’t let anyone else sit in his chair on the set.”

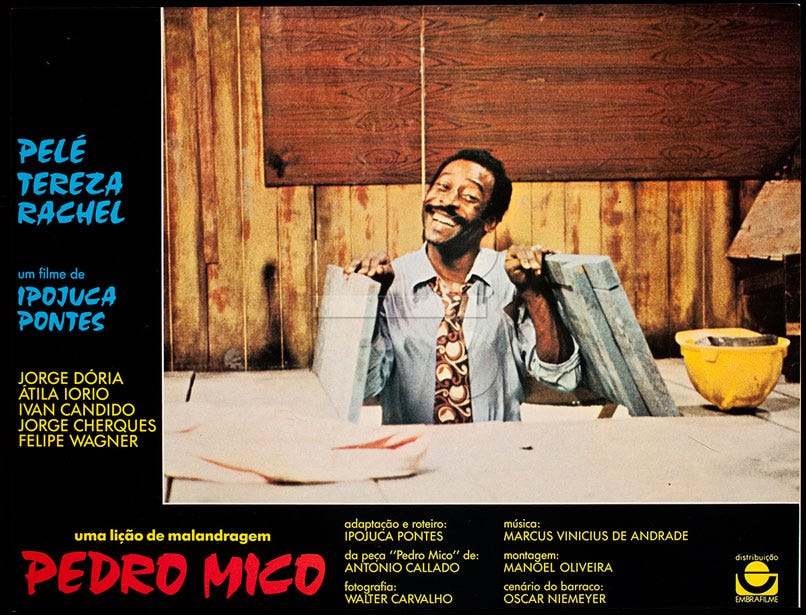

In the Brazilian crime thriller Pedro Mico (1985), Pelé, as the titular Rio trickster, showed off some capoeira skills—and an impressively bushy mustache—in what would be his only lead role. After Pedro Mico, however, Pelé settled into a groove of mostly appearing as himself in fictional films: a testament to his star power and his gift for self-marketing.

He re-teamed with John Huston for the syrupy but affecting orphanage fable A Minor Miracle (1983), then grew a beard for and wept in 1987’s syrupy but affecting soccer drama Hotshot. Some years later, he had a brief and very funny appearance in Britcom Mike Bassett: England Manager (2001).

There are enough hints in Pedro Mico to suggest that Pelé could have had a more substantial acting career. But it seems, understandably, he decided that being the world’s greatest soccer player was more than enough.

And that’s it for now. Let’s play out with some more Brazilian magic: “Toda Menina Baiana” (1979) by the very great Gilberto Gil. This was one of my favorite songs as a kid, and it still is today.

Until next week!

Thank you for reading. Please consider subscribing to this newsletter if you’ve yet to do so, or, if you have, spreading the word. I appreciate it!

If you haven't already listened to it, Brian Phillips final episode of his "22 Goals" podcast was on Pele and the '58 World Cup.

And I did enjoy his Mike Bassett cameo. Not sure how "Christ, it's the English" hasn't become a meme yet.