"Let’s turn this logic on its head...": In conversation with John Akomfrah

An in-depth chat from 2018

Thank you to everyone who has subscribed to this newsletter. If you’re coming back for more after laying eyes on that gruesome Nelson Mandela/Crocodile Dundee hybrid from my first post, you’re made of strong stuff, and I salute you.

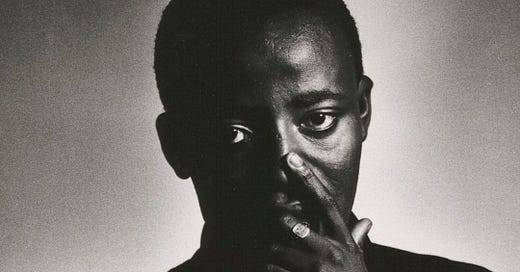

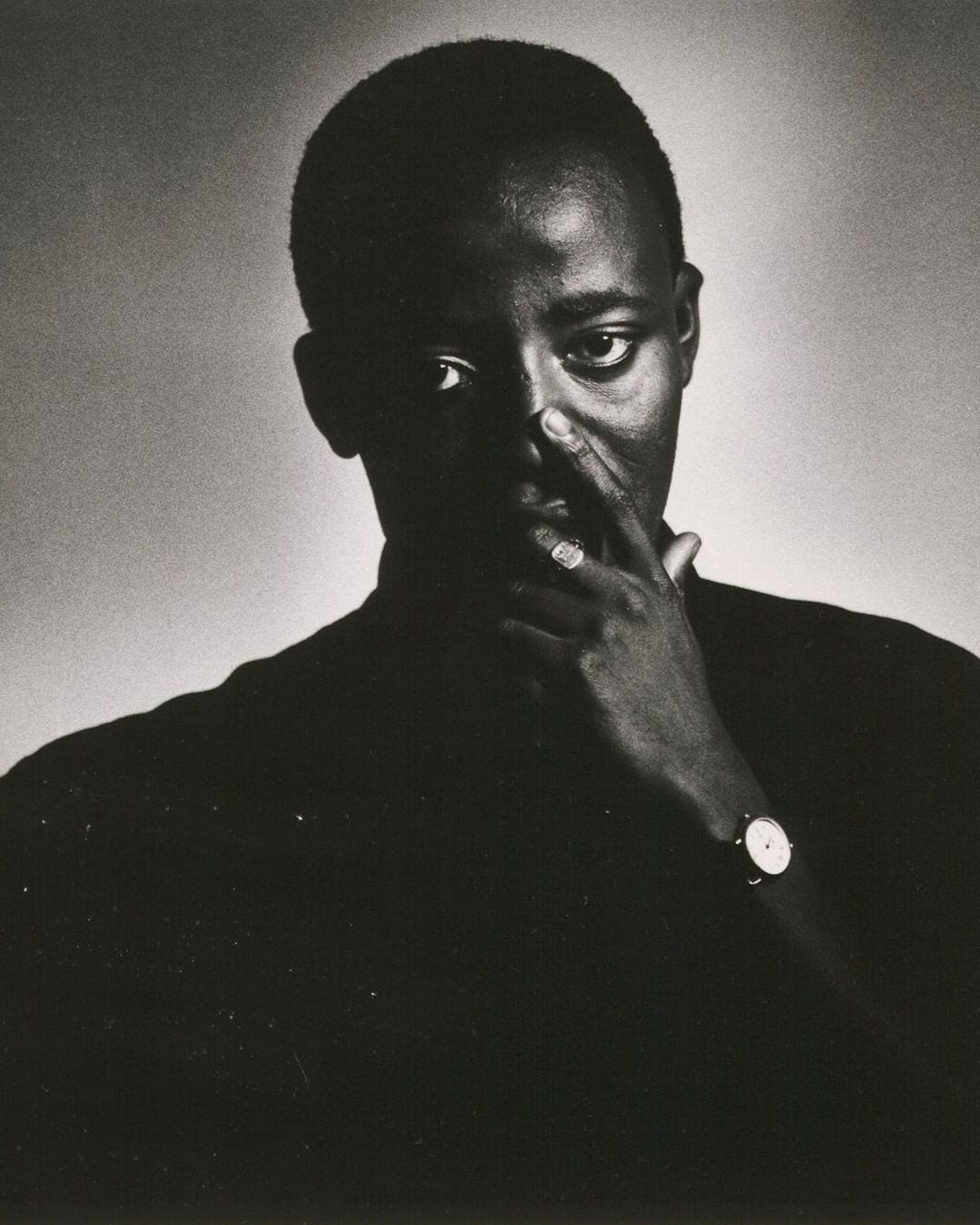

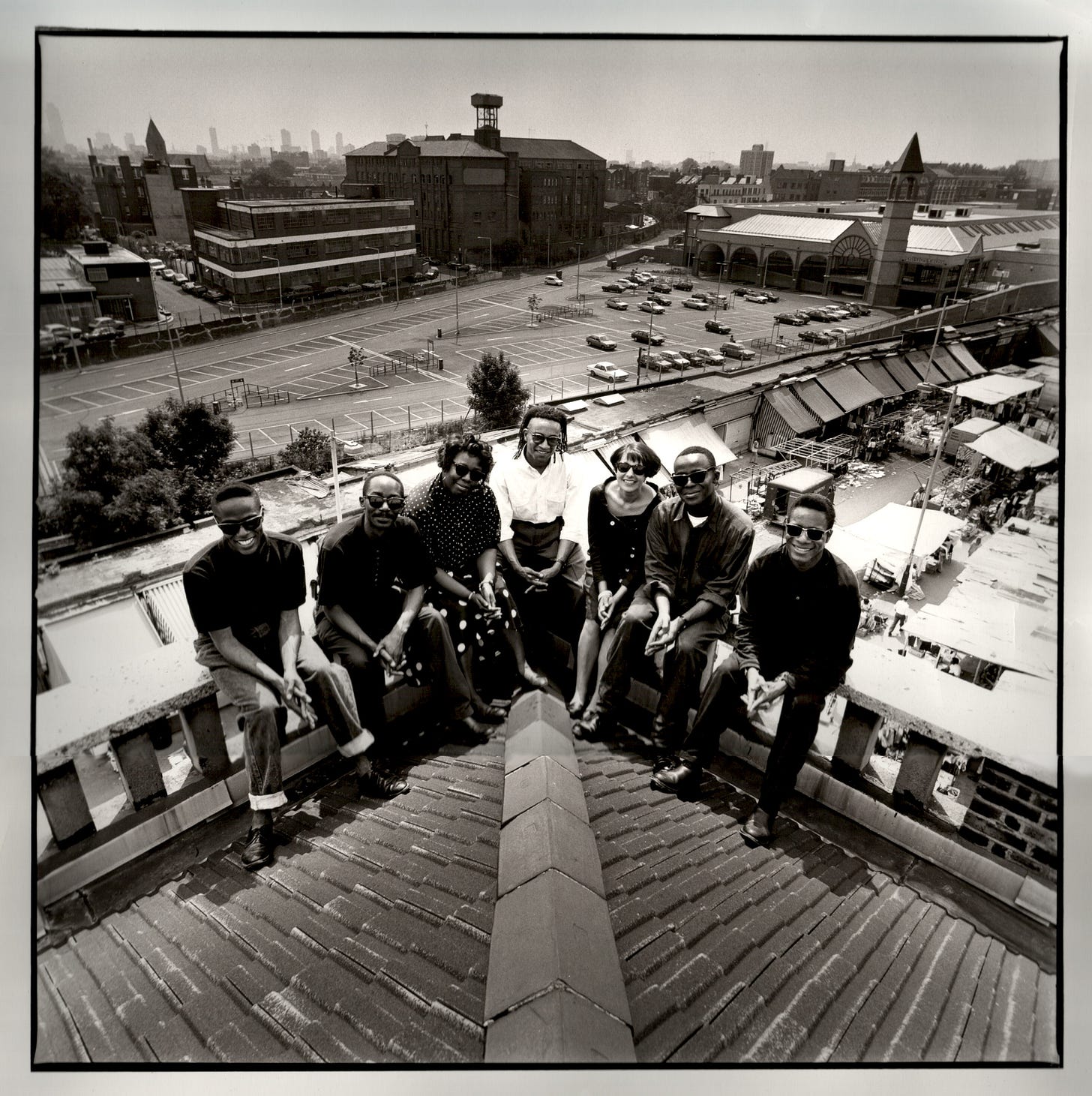

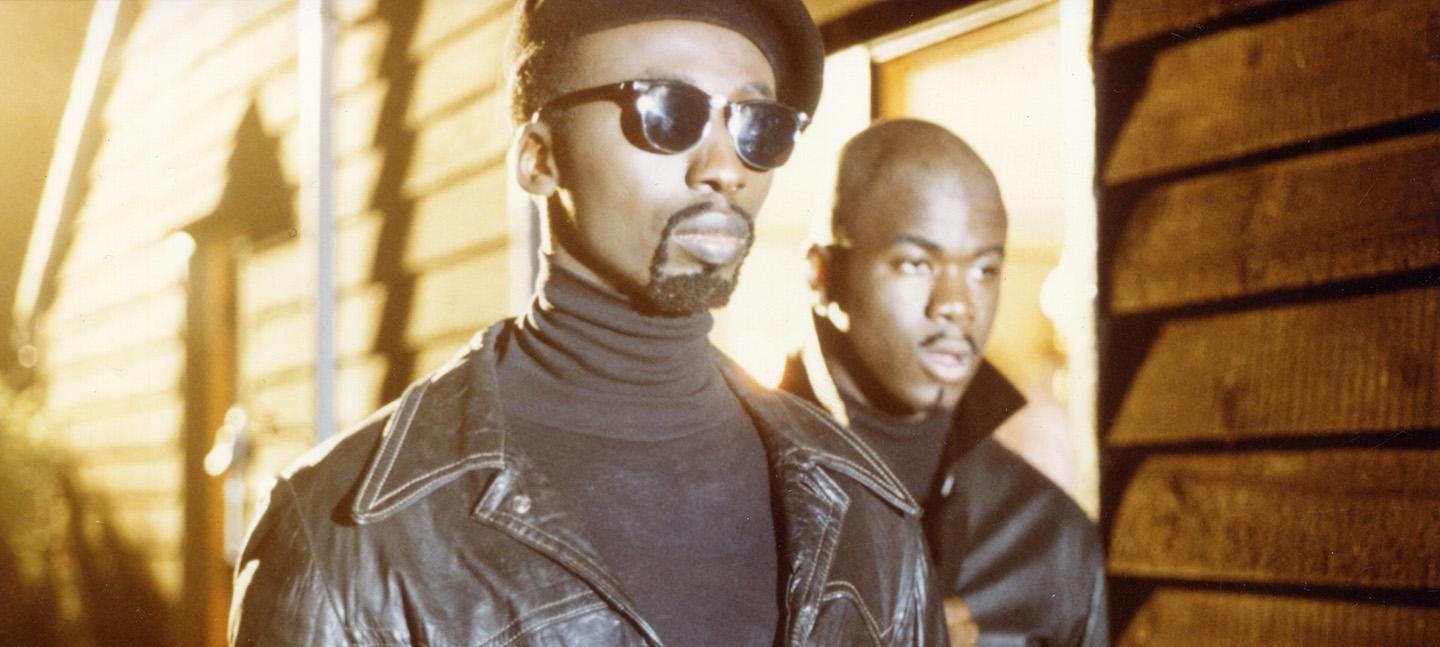

One of the ways I’m keen to use this space is to publish old interviews and features of mine that have never appeared online, or have been published in some truncated form. What follows here is a wide-ranging and, I think, rewarding conversation between myself and the British Ghanaian artist and filmmaker John Akomfrah from January 2018. The interview was first published in February 2018 in a limited edition print monograph accompanying a program I organized for the True/False Film Festival in Columbia, Missouri, that celebrated the work of Black Audio Film Collective, the trailblazing group formed in 1982 by Akomfrah and six artist colleagues. The full PDF of this monograph (which was edited by the brilliant and innovative programmer-writer Chris Boeckmann), is available on Issuu, but this is the first time this interview has been available online in discrete, easily accessible form.

John is one of my favorite artists to speak with. He is gregarious, generous, learned, and witty, and I always feel the thrill of having my horizons broadened in real time. I hope you enjoy.

Ashley Clark: You moved to London from Ghana at a very early age. Can you talk about some of your formative artistic experiences?

John Akomfrah: I grew up in West London, in fairly close proximity to places that would essentially define my life. There was an independent repertory cinema called the Paris Pullman on Fulham Road, and I started going there when I was 13, 14 years old. The other was the Tate [then Gallery, now Tate Britain], which was fifteen minutes walk from my house; I would wander there on Saturday mornings. As a young, black kid interested in culture in the 1970s, I never really thought that those three defining features of my life would come together one day: the fact that I was black was a kind of accident that had to be overcome. If you had told me when I was a 12-year-old that I would end up working in a space defined by blackness [BAFC], I would have laughed at you because it didn’t seem important. And if it was important, it seemed like something that one had to “overcome”, because it was clear that it was going to be an impediment in some way. When I went to the Tate, I didn’t see many artists of color; when I went to the Paris Pullman, I didn’t see many films made by people of color. So I assumed at the time that the thing to do was to not gravitate in those directions.

It’s only later on that I thought, hang on, let’s turn this logic on its head—since I’m not really seeing anyone making stuff who looks like me, and I’m not seeing work in the Tate about subjects that I might be familiar with, maybe this might be something that I could do. But it took all kinds of other historical interventions by society at large to make that possible. In 1976, the disturbances in West London—the Notting Hill “riots”, as they were called—were a critical turning point for my generation because it suddenly became apparent that there were certain paths that you were not going to be able to avoid walking down. It was clear from the way in which those disturbances at the Notting Hill Carnival were described, talked about in my area, that everyone who lived on my street, the majority of whom were white, and fairly well-to-do, just assumed, in their minds, that I was one of those kids throwing bricks at the police: you could see it in their face. At that point, I just thought, I’ve got to turn around and confront this. We have to do this.

Can you talk more about these formative experiences of being black and British, and how it affected how you saw the world?

I remember writing this thing about how we [BAFC] drifted toward the work of Stuart Hall, and some of it was to do with one of these moments. I think everyone my age, who came of age in the 1970s, had this adventure with what I call the “doppelgänger”, the double. There was this talk in society about the figure called “the black youth”, and this black youth was a criminal, mugging, fearful creature. You heard about this figure, but you didn’t think that it had anything to do with you, and then—and everyone I’ve spoken to experienced this—there’s a mirror moment when you suddenly realize: fuck, they’re talking about me! At that Fanonian moment, you think, OK, either run even further away to escape this doppelgänger moment, or do the opposite, which is to head towards it, to claim it, to fuse with it, or essentially to make friends with it. On the whole, most of the people in the collective came together because we’d decided to make friends with it. It was like, oh well, since I am supposed to be this creature, I’d better get to know it, I’d better become it, and learn how to get it to speak in the way that I want to speak. Not this slightly weird mumbo-jumbo that The Sun newspaper [a widely-read right-wing British tabloid] gets it to say. We’d better get it to say something that makes a little more sense to us.

Let’s talk about the group coming together at Portsmouth Polytechnic, where you would become Black Audio Film Collective—what drew you together?

In the 80s and 90s, we spoke a lot about the question of multiplicity, the fact that we came from these different class and professional backgrounds. But the single most important thing was this weird “Fact of Blackness” that forced us together. Modern neoliberal capitalism has tended to break people down into smaller and smaller molecules so that, if we were working today, we may not have ever come together. Yet this backdrop of race functioned almost as a kind of glue. I had gone through further education [in London] with Lina, Reece and Avril, and met the other members, Trevor, Edward, and Clare, in Portsmouth. I stress this backdrop of race because even though we were on different courses, the glue was this host of black student societies, discussion groups and informal college circuits that basically forced people of color into reflecting on their circumstances. Portsmouth is a fairly mainstream white city [on the South-East coast of England] with a slightly unpleasant right-wing edge, so if you found yourself on your own, wandering the streets at night, it was quite likely that one would be attacked by a group of skinheads, or a member of one of those extreme right-wing groups at the time. It was, then, in your interests to band together and form associations and solidarities—most of us met through these informal networks because people were black in a hostile white space. We tended to not speak too much about it, and it gave the whole thing a kind of romantic air, I’m not going to deny it. We were not your average or typical black students at the time. For one, most of us were interested in cultural politics, and the cultural politics of the avant-garde, and that wasn’t typical.

When did you come up with the name?

It would have been 1982, at Portsmouth, when we were doing a series of installations for a number of festivals that the Afro-Caribbean society was organizing. We knew that the show would have sound design elements, and projections. We needed a name that would describe the multifarious nature of what we were interested in, and it became clear that whatever we were going to become, it would be in large part brought about by this fusing of multiple interests. Black Audio Film Collective seemed to suggest that hybrid form. I can’t remember now who came up with it—I suspect that, like everything we did at the time, somebody would have suggested something, we would have discussed it, and then we would have kicked it to somebody else. We were like the quintessential collective: lots of discussions and not much doing! Lots of talk and not much action [Laughs] The name would have been the result of very, very, very many conversations, believe me!

In the group’s first official statement, which was published in ArtRage magazine, the aims go beyond simply making the work itself. Can you talk about those key goals?

Well, by the time I got to meet most of these guys at Portsmouth, I’d had over a decade of looking at really serious works by both the political and the aesthetic avant-garde—the New German Cinema, the New Latin American cinema. Some of us had run a film club while at school in the 1970s, and at Portsmouth there were various film societies. The thing that we had picked up was that all of the successful artists politically, aesthetically and culturally, emerged in spaces of crises, and these spaces were not just aesthetic but cultural. The Argentinean filmmakers, Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, who made The Hour of the Furnaces (1968), were actively engaged in cultural and political circles, as were the German and French New Waves. We knew that making stuff in itself wasn’t enough. It also needed to find a way of accessing our uniqueness and specificity as black British folk—it was easy for us to understand that, because there weren’t many people of color in Britain who wanted to make films, or artworks. At the first Black Arts Conference in 1982, there was something like fifty of us in the room, out of the whole country! The work had to be nuanced if it was to stand any chance of success, but you couldn’t just make films and hope people would see them. We were active in making spaces available so that people of our generation who hadn’t had the luxury of going to university or art college, or studying for degrees, could see that what we were doing had some relevance for them and their lives. We were trying to think about ways of creating a subculture in the broadest sense. It also meant making audiences, and trying to come up with new desires for how our generation worked. We knew this could work, because we saw how it worked in music. From the ages of 16, 17, we saw the galvanizing function of music in black youth life. We went to concerts and clubs, and you could see when something had a cultural appeal, it just gripped people. You’d go to these blues dances and it would be pitch black, you’d be in there for hours and hours journeying through basslines and rhythms. You knew that it wasn’t a question of black backwardness when it came to culture. It was about trying to find something that held out the promise of engagement for people of your generation. At the time, that was the uppermost thing in our mind, the key obsession: How do you make work which is challenging and difficult and reflective and questioning but spoke to people just like you, from your background, your generation? The extent to which we managed that is a moot point, but desires and ambitions need not necessarily be met fully for them to be realized.

Speaking specifically to the title of this festival, True/False, much BAFC work deliberately blurs that so-called line between fiction and non-fiction filmmaking. Coming to the work, did you ever see fixed boundaries?

I’ve always loved the work of the Cubans and French filmmakers, especially Alain Resnais — Night and Fog and Last Year at Marienbad were really important films for me and for some of the other [BAFC] members. We were always interested in the Borgesian idea of “the blur”, the merge of multiple worlds and spaces, in a way that made the distinction between fact and fiction seem irrelevant. When it came to the circulation of race in the political imaginary, the distinction between fact and fiction was completely spurious. What was circulating was precisely this fusion of fact and fiction; you needed to get your head around that. There was no point going up to people and saying, “I know you saw that black kid on the news mugging people but that’s not me — the majority of black kids do not do that”. This almost journalistic appeal to veracity and truth wasn’t useful because we seemed to have been doing that the whole distance, and it didn’t do us any good. We just had to look at our parents: they were upstanding members of the community, most of them worked like dogs, they didn’t do anything wrong. The thing that scared them more than anything was that we would get into trouble. They led these quietist lives of piety and devotion to work and their homes. That was the truth of their lives, but that was not the circulation of blackness in the culture. In the circulation of the news, in the culture, “these people”, meaning our parents, were scroungers, dirty… the discourse of race had nothing to do with truth.

Following on from that, for a long time, pre-Channel 4, it was effectively down to one state broadcaster (BBC) to set the tone for news, to convey to the public the “real” version of what’s happening. How important was Channel 4 culturally?

It was really important in a way that’s almost impossible to describe now. The transformations that it helped bring about have been so complete that it seems like not just another era, but another universe. I know there’s subtlety and nuance and complexity in the non-fiction work and documentaries that were being done before Channel 4 came about, because I use them all the time in my work. But there was something else that came with Channel 4, and that was the emergence of a unique and new paradigm that wasn’t licensed by the conventions of journalism, or the patrician class, or a tradition of radical Griersonian filmmaking which itself was a sort of patrician form. What Channel 4 did more than anything was to introduce a whole nation to the idea of the image as a thing of reflection rather than of statements, or enunciation, or social policy, or political dialogue. It said that images can be ambiguous. You can look at them in a variety of ways. Before Channel 4, the majority of images came tied to the voice, some sort of speech, a voiceover, monologues, reminiscences—they were virtually imprisoned by the voice. Then, for the first time, in 1982, you could sit and watch a program, say, So That You Can Live (1982), about the border country of Wales, made by an avant-garde political collective in London [Cinema Action], and it had a quarter of the words that you would normally hear in an hour’s program. It was like “wow, what’s this?”, not because I didn’t know about that work, but because I’d only associated that way of things with working outside of television. We went to the cinema to escape the squareness and cultural illiteracy of TV; the cinema was where we’d get together and watch stuff like this with like-minded people. Suddenly it was on television, it was open to everyone, not just you and your mates—it’s now like a national address.

Today, there’s a mixed economy of narrative and narratological approaches that you see all around you, but back then this was a genuine alternative to the entire audiovisual edifice that you’d known your whole life. It was a new space, on your street! I would go out occasionally and stand on a different street from the one we lived on, just to see which lights were up. Were they watching Channel 4? Because it was the only thing that was going late at night. Suddenly there were all these lights on streets. A new community of the night was emerging, most of whom were watching The Eleventh Hour [a weekly late-night specialist screening slot specializing in independent and experimental film and video], Latin American cinema, the films of Derek Jarman, Malcolm Le Grice, Chris Marker, people who just had not been visible on television for my whole life. I was in my 20s and I’d never seen anything like this on television. It was seismic.

It must have been a thrill, then, to have Handsworth Songs be broadcast on Channel 4?

Most of us who got to work for Channel 4 had to really fight for the right to do it; you couldn’t just walk in. We had to really earn the right, so we needed to first work between ourselves in the Independent Film Associations (IFA) to come up with a strategy for our way of working, and then we needed to persuade the ACTT about the desirability of having us, then we had to persuade the commissioning editors. There was no taking for granted the fact that Handsworth Songs would end up on Channel 4. There was no natural progression from where we were, to it being on television. It had to be passionately fought and argued for. The difference was that Channel 4 seemed worth it, because it was trying to do something genuinely radical and subversive.

When BAFC came to an end in 1998, was it external pressures telling, members wanting to do different things? Did it feel like the right time to go in a new direction?

It was a combination of factors. Half of us had met when we were 17, 18, 19, so by then we were in our 30s—it’s almost impossible to keep that many people growing in exactly the same way, as different interests emerge. The biographical seed in the machine was beginning to change. There were people who were, for instance, partners who weren’t partners anymore, in a romantic sense, and those things start to impact on what you can do and how you do it. By 1998, Channel 4 had changed beyond recognition. The spaces that it had opened up were now being commandeered and reintegrated into the mainstream. In the early days of Channel 4, many of the commissioners were people from different walks of life. Rod Stoneman and Alan Fountain, who were heads of film and video, were not TV people. By 1998, 99.9% of people who ran Channel 4 were ex-BBC commissioners and editors, producers or directors. It just seemed as if it were a branch of BBC. Culturally, there was also a sense that many of the tropes and narrative strategies that we were trying to deploy, all of which were meant to hit something about the complexity of black subjectivity, had taken root. People were like: OK, we get it. We understand [laughs]. Many of these strategies that we used to render more nuanced pictures of black life had been absorbed, sponge-like, by the mainstream. Increasingly, it seemed were kind of anachronistic. People would say, “We’re already doing this. What’s your problem? Why do you want to keep banging on for the need for what you’re doing?”

Finally, most collectives have a built-in obsolescence. Collectives come about, in large part, because of the things they want to achieve. Many of those things are usually autobiographical in origin and cultural in outline. Invariably, once you start to feel those things have been achieved, it’s very difficult to keep on going. In many ways they shouldn’t keep going. I’m now of the opinion that there should be a sort of time limit with collectives [laughs]. When you start off as one set of people and you work for 17 years, it’s extremely likely that at the end of your 12th or 15th year many of the things you want to achieve you will have achieved personally, or it would be nowhere in sight. Both reasons, to me, seem to require some giving up. If you can’t achieve it’s likely you’ll need to rethink your strategies. To reformulate, that’s what we’ve tried to do. Myself, Trevor [Mathison], David [Lawson], and Lina [Gopaul] all wanted to continue to work in time-based spaces, simply to find new allies and collaborators, and we just got on with it.

Further reading:

An introduction to the work of Black Audio Film Collective for Film Comment magazine by yours truly, back in 2014.

Me again, with a potted history of Black British protest cinema, for Sight & Sound in 2020.

A terrific interview with John from The New York Times from September 2021.