Hello! Thank you for signing up for, or stumbling on, this no-news-newsletter written by me, Ashley Clark. If you do subscribe—and it’s free—you’ll receive occasional bulletins about whatever’s on my mind: usually some combination of art/film/music/literature/football. If that sounds good, hit the button!

One of the ways I’ve been using this space is as a venue for previously published written work of mine that’s either disappeared from the internet, or never was there in the first place. The following falls into the latter category. Back in 2016, after years of heroic work in the rights clearance and restoration departments, the BFI released “Dissent and Disruption: Alan Clarke at the BBC, 1969-1989”, a comprehensive set dedicated to the TV work of the iconoclastic British filmmaker who died in 1990. I wrote a couple of essays for the book that came with the set, on Scum (1977), and 1982’s Baal, an adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s 1918 debut play that had previously been filmed by German filmmaker Volker Schlöndorff with Rainer Werner Fassbinder in the lead role. Baal is a tough watch, but I found it rewarding to write about, so read on for the essay, presented here with a few minor tweaks and—hopefully—improvements (less adverbs, basically.)

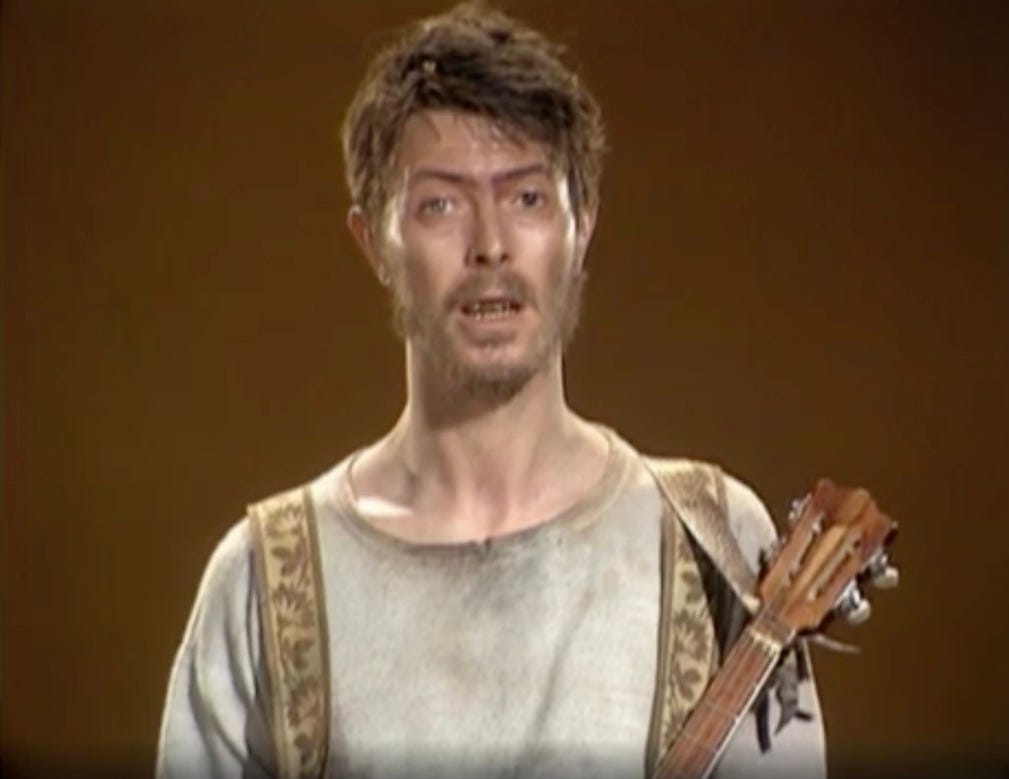

After David Bowie’s death from cancer at 69 in January 2016, obituaries which focused on the singer’s eclectic acting career tended, understandably, to cite his higher profile roles, including the fragile, off-white extraterrestrial Thomas Jerome Newton in The Man Who Fell To Earth (1976); tragic soldier Jack Celliers in Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence (1983); or the pompadoured Goblin King Jareth in Labyrinth (1986). Very few mentioned his startling turn as the eponymous, dissolute poet/musician Baal in Alan Clarke’s TV adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s first play, which the German author wrote in 1918 while a 20-year-old student at Munich University.

Baal, which first aired on BBC1 on March 2, 1982, has long been widely unavailable to view (legally), and is regarded as an obscurity in the respective canons of Bowie and Clarke. It finds both its director and star in boldly experimental mode. Clarke stages the play in devoutly non-naturalistic fashion, with split-screen, narrative framing sequences featuring Bowie-as-Baal singing flatly descriptive songs to camera; emotionally distancing, long-lens captures of artificial interior tableaux; and obviously fake outdoor sets made of gauze. Bowie, meanwhile, slithers into the sweaty skin and dirty clothes of this troubadour — named after a 17th-century demon said to appear in the forms of a man, cat, toad, or combinations thereof — to deliver a remarkably unsettling, shark-eyed performance. Even allowing for Bowie’s chameleonic credentials, it’s hard to process that the grimy Baal is being played by the same man who would, a mere year later in 1983, attain global fame as a zoot-suited, peroxide-coiffed crooner on the Let’s Dance album and subsequent “Serious Moonlight” tour.

Baal’s episodic narrative follows its protagonist over a number of years, and unfolds like a forbidding, implacable lullaby. It’s quickly established that Baal is equally fond of booze and women (“Dawn to dusk, his bed not allowed to cool off!”, comments one minor character.) He begins by pugnaciously rejecting an upper-class benefactor interested in subsidizing his poetry. He seduces (or, more accurately, statutorily rapes), then leaves, the 14-year old Johanna (Tracey Childs), who subsequently drowns herself. He acquires a mistress, Sophie (Zoe Wanamaker), then impregnates and casually abandons her. He murders his only friend Eckart (Jonathan Kent), and becomes a fugitive from the police. Baal, who never once shows remorse for his actions, eventually dies alone in a woodland hut, hunted and deserted.

Baal is challenging viewing, notable for its stylistic coldness, and the relentless bitterness of its content. “I marveled that anything so bleak, austere and radical could possibly have been screened at 9.25pm on a Tuesday evening on BBC1,” wrote TV expert John Wyver in a 2013 article. It is indeed difficult to imagine anything comparably dark and weird airing in a similarly prestigious national slot today, and its singularity is only intensified by the high-profile nature of its star-director collaboration. Clarke had, by that point, acquired a strong reputation as a creator of 15 years worth of challenging TV drama, while Bowie’s fame spoke for itself.

Bowie is brilliant here, and possibly quite influential. With his wiry-legged lope, ratty facial hair and verbose philosophizing, Bowie’s Baal feels to me like the progenitor of another consummate outsider: Johnny (David Thewlis), the sexually rapacious intellectual bully who stalks the glum London streets of Mike Leigh’s Naked (1993). These two dastardly wastrels — both intriguing outliers in the oeuvres of their respective directors — share a magnetic charisma which compels the vulnerable helplessly into their orbit. Baal’s aggressive disrespect for women, for example, is remarkably Johnny-like; consider the disturbing sequence which finds Baal slashing at his own hyper-realist, gynecological artwork with a knife, in-front of Sophie, who seems strangely transfixed (the name of cruel Johnny’s most tragic conquest is also named Sophie, played by the late Katrin Cartlidge.) Likewise, both characters are incarnated by performers whose skill ensures the viewer is awkwardly pinned between the polar realms of repelled and compelled.

The character of Baal was conceived by Brecht as a parodic rebuttal to Hanns Johst’s expressionist piece Der Einsame [The Lonely], about an unacknowledged artist who redeems his dilettantish lifestyle and dies at peace with the world. There’s no such redemption for Brecht’s monster. Yet one senses that Clarke had a certain fondness for Baal’s disdain for the bourgeois establishment, and the mischievous, glaze-eyed glee he takes in causing offence. Following a club performance in which Baal mimes vigorous anal sex with Zoe onstage, the proprietor threatens him with censorship, and threatens to call the police. Five years earlier, in 1977, Clarke had himself been the victim of establishment censoriousness, when the BBC’s director general Alistair Milne opted to suppress his original television film of Scum, ostensibly on the grounds of excessive violence and presenting an exaggerated picture of the failings of the borstal system.

Some of the critical response to Baal, meanwhile, featured the kind of hyperventilating and hand-wringing that would have surely delighted Clarke. “[A] total flop,” railed The Daily Mirror’s Hillary Kingsley. “I cannot believe even the most besotted of David Bowie’s fans could have tolerated more than a few moments of it … That the BBC could spend a small fortune on this repulsive and rightly ignored tableau is a cause for top level concern.”

Speaking to biographer Richard Kelly after the director's death, the producer David Jones spoke about the parallels between the iconoclastic Clarke and Brecht’s complex anti-hero. “Baal is a character Alan would identify with – profoundly, you know?", he said. "I had this feeling about Alan that some of his fun and sparkle and natural comedy became a little outweighed by a certain pessimism as he got on. And sometimes that made his work a little more aggressively bleak than it needed to be. Baal is a very young play – a subversive comedy, basically – whereas I got the feeling Bowie’s Baal was being pressed into a kind of martyrdom.” Baal might well be short on laughs, but it's a strange, powerful work, and a document of two rare artistic talents working in uncompromising harmony.

Bonus Bowie, because this most overwrought couplet is rarely far from my mind. Sing it with me: “Time! He flexes like a whore! Falls wanking to the floor!”

Thank you for reading. Please consider subscribing to this newsletter if you’ve yet to do so, or, if you have, spreading the word. I appreciate it!